The Remarkable Story of Dewey Bozella: Boxing Saved Me

Ten years after being released from prison for a murder he did not commit, Dewey Bozella tells how the sport gave him purpose and talks of his fight to change the New York State laws that put him away

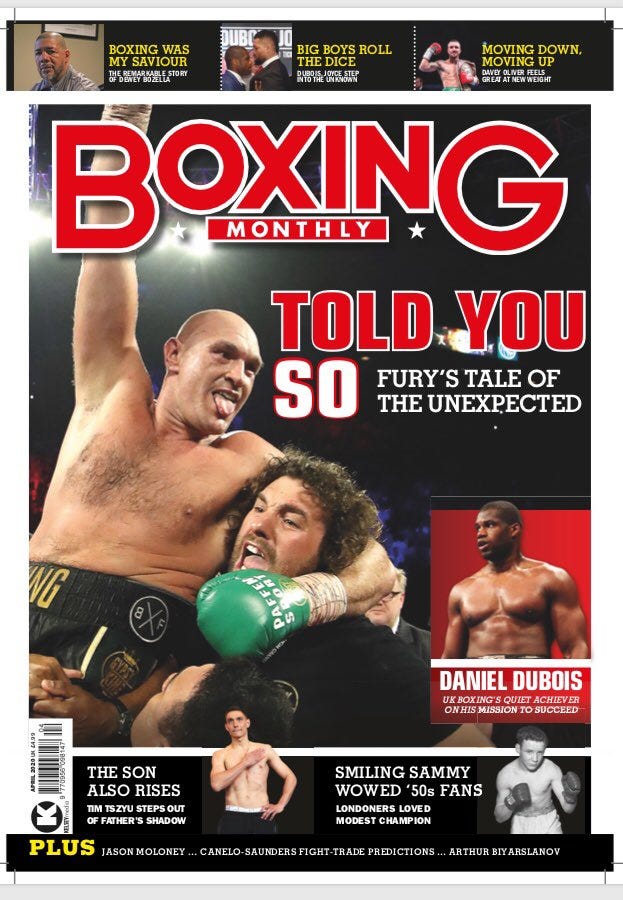

This story was originally published by me in the April 2020 edition of Boxing Monthly, a popular and well-established London-based boxing magazine that has produced exceptional content on the Sweet Science since 1989. Sadly, after 31 years, it was announced in March that Kelsey Media, which purchased the magazine in 2018, will cease the print and online publication in June. This story was supposed to run on the website but unfortunately the site is expected to shut down as well, so I wanted to create an online version of the story for the readers. This version of the story is an extended version from the one running in print.

Bang! Boom! Bang!

The loud sounds of thumps reverberated across the gym.

The effort. The strain. The force. As hard as the man was pushing himself, you’d think he was preparing for combat.

First, Dewey Bozella shadowboxed for seven minutes, gauging his every move through the mirror wall to make sure his form was airtight. He then laced up the gloves and attacked the punch bag.

It was as if he was punching out frustration from all the low blows he’s had to endure from society over the past four decades.

You can see the scars of everything life has thrown at him through his raw intensity. It’s like he’s releasing the inner pain from within with every potent strike.

I’d hate to be the bag at that moment.

When it was time to hit the pads with his trainer, a full sweat was already worked up in the frigid gym this Tuesday afternoon. This next session is the night capper.

Mistiming plays a factor early on but Bozella soon gets his rhythm back throwing a variation of punch combinations. One-two jab-right cross punches. Double jab-right crosses. Straight right-left-right-lefts. Double left hook-right crosses. Double jab-straight rights. Uppercut-left hook-body shots. Double right hook-jab-crosses. It’s all on display.

Then it’s a wrap.

Exhausted in the corner, leaning on the ropes and taking in deep breaths, Bozella looks both dog-tired and pleased.

“Damn. I needed that,” he said.

Asked when was the last time he had a full boxing workout, he replied, “It’s been awhile. Too long actually. I’ll definitely be in here more often.”

Boxing trainer Kariym Patterson, who trains youths and older people at his APJ Boxing Club in Poughkeepsie, New York, acknowledges that he was rusty during the pad exercise but settled in quickly. “Well, he’s still sharp. I don’t have to say much. With the younger guys, you kind of have to coast them through things. With him, I don’t have to do much because he knows what’s going on. He’s been in the sport for a while, so he has a high boxing IQ,” said Patterson.

Boxing trainer Kariym Patterson puts Bozella through his paces in the gym at Poughkeepsie, New York. Photo Credit- James Simpson II

If anything, Bozella has had to stay sharp and on top of things, not just in the ring, but out in the world that has let him down so many times before.

If his continued existence proves anything, it’s that this game of life can take you down an unexpected path of obstacles that can shape you for better or worse.

******

Dewey Bozella has never been a stranger to hardships. They’ve followed him throughout his life. Attached to the hip and difficult to break off. The tribulations seemed never ending.

From the uneasiness of growing up as a light-skinned kid with a white father and black mother in a predominantly black neighborhood in Brooklyn during the segregated 1960s to, at nine-years-old, when his pregnant mother was murdered by his abusive father, to bouncing around to different foster care homes to, at the age of 16, losing his brother Ernie, who was stabbed to death outside a school dance.

Then came the earth-shattering event when he was arrested for burglary and the murder of 92-year-old Emma Crapser in 1977 in Poughkeepsie at the age of 18, with the charges being later dropped because there was no evidence linking him to the crime. Six years later, in 1983, he was rearrested, convicted of the murder and sentenced to 20 years to life in prison in the Sing Sing Correctional Facility in Ossining, New York.

Over the course of the next 26 years, life presented one mega fight after another for Bozella that he had to face head-on and endure internally. He was given a retrial in 1990 but was convicted again and sentenced to 20 years to life for a second time. He was denied parole on four different occasions. While in prison, he was given crushing news that his older half-brother Tony was murdered and his younger brother Leon died of the HIV/AIDS disease. Still during that period, Bozella vehemently maintained his innocence even when he was offered plea bargain deals that would have allowed him to walk free if he confessed to the murder. Bozella stayed firm to his truths and finally on October 20, 2009 he was fully exonerated and released from prison due to evidence being suppressed by the prosecution. Bozella was a free man and later filed a federal civil rights lawsuit where a settlement of $7.5 million was agreed upon.

His story became national news. It was on every news outlet you would turn to. He became a symbol of perseverance through dealing with the most unfathomable of circumstances that an individual wouldn’t have ever imagined experiencing.

Ten years later at the age of 60, Bozella stands as upright as ever. He lets me know that prison didn’t break him. Many men would have succumbed to the desolation of being locked up behind stony walls. He wouldn’t let it.

Although his ring career was limited to one bout, Bozella was presented with a WBC belt in recognition of his struggles against the odds, while the WBF Inter-Continental championship belt was given by heavyweight Amir Mansour. Photos on the wall at his home show Bozella at the 2011 ESPY Awards and in his first and only pro fight. Photo Credit- James Simpson II

Asked what he took from being locked up for that long, Bozella’s answer is directly tied to the message he wanted to send the audience that read his 2016 memoir Stand Tall: Fighting For My Life, Inside and Outside The Ring. “More or less, don’t give up. If you believe in something, are you willing to die for it?”

While locked up, Bozella discovered purpose. “I had to find myself in there” he said. He got his education by receiving a GED and 52 certificates. He earned a bachelors degree from Mercy College in Dobbs Ferry, New York, and a Masters degree from the New York Theological Seminary. He got married. When word spread that the man who killed his brother Ernie was in Sing Sing, he confronted him face-to-face and found the strength to hug and forgive his brother’s killer, an act he says was a “real test” in that moment.

Although, if there is such a thing as finding a lasting positive effect while being incarcerated, then Bozella found it in the sport of boxing. Boxing was his healing in uncertain times. His escape route when all things failed. His solitude when chaos and uncertainty surrounded him. “This is what saved my life when I was in prison,” said Bozella. “This is what put me in a better position and helped me survive. This is what I was meant to be doing.”

******

Bozella started boxing at the age of 19. “I was a street dude and I would get into a lot of street fights in Poughkeepsie. Since I fought a lot in the streets this dude said to me, ‘Since you like to fight so much, why don’t you go to Floyd Patterson’s Boxing Camp?’ So, I went to his boxing camp off a dare,” said Bozella. The former heavyweight world champion’s camp for young fighters was located in New Paltz, New York, where Bozella attended high school. “Once I learned that I can take a punch, I fell in love with it.”

What intrigued a young Bozella the most was the challenge of learning how to fight. He learned how to pace himself, gain stamina, move in the ring and how to adjust by sparring different partners.

During the era of the 1970s, boxing was at the forefront of the American sports landscape and Bozella drew inspiration from greats like Muhammad Ali, Joe Frazier, Roberto Duran, Wilfred Benitez, Sugar Ray Leonard, Danny “Little Red” Lopez and Marvin Hagler. Soon Bozella became a boxing fanatic, taking a trip down memory lane. He would go out to the movie theater in Queens, New York, where people would pay to watch the big fights.

“At the theater is where I saw some of the best fights ever. I saw the Ali-Frazier fights. The fights when Ali faced Norton and Foreman were real good. Frazier vs Foreman was something. When Sugar Ray Leonard fought Wilfred Benitez, that was a great fight. That was a 15-rounder. Guys today don’t understand what it’s like to go fifteen rounds,” said Bozella. “I thought in a couple of years, I’ll be doing this as a pro.”

Before Bozella got the chance to pursue his goals, he was arrested for murder, then six years later, rearrested and thrown in penitentiary. Locked up and shut out from the outside world, all hope seemed lost. Gutted that not only his freedom was taken away but his dreams as well, there was no where to turn in Sing Sing. He soon found a ray of hope in Sergeant Bob Jackson, who started a boxing program at the prison. Bozella pounced on the opportunity.

“He gave me discipline,” recalled Bozella. “He told us, ‘If you get in trouble, you’re off the boxing team.’ He gave us videos to watch, worked out together, ran and he gave me something that is important to me.”

What Bozella lost in the real world, he gained back on a small-scale in prison. He dedicated himself to the sport. He trained relentlessly. He studied tapes of Ali and Marvin Hagler, who he aimed to mimick the most. “I was more of a stick-and-move fighter,” said Bozella, explaining his fighting style. “Once I see your tired, I’m going to come right at you. I don’t walk in without throwing punches. I’m throwing punches. I wouldn’t slug with you but I was more of a boxer-slugger.”

Bozella attacks a punchbag with authority during a workout at the APJ Boxing Club in Poughkeepsie, New York. Photo Credit- James Simpson II

Over the years, Bozella carved out an identity for himself and became the light heavyweight champion of Sing Sing, compiling a 9-1 record. “I didn’t get a belt but it was more like a title and label that was being thrown around about me,” said Bozella. Although, his biggest test in the ring came in 1990, at the hands of Golden Gloves winner and eventual WBA light heavyweight champion Lou “Honey Boy” Del Valle, then still an amateur boxer and who is best known for being the first fighter to knockdown the best pound-for-pound fighter of the 1990s in Roy Jones, Jr. — in a unification title bout in 1998, in which Del Valle lost.

“The fight got stopped in the second round because of a cut on my eye,” Bozella said. “He didn’t knock me out or knock me down. He hit me with some good punches and I hit him with some good punches. I gained a ton of respect in prison for that fight.”

Over the next two decades Bozella continued to box and fight for his innocence, then in 2009 the day he had long waited for arrived when his murder conviction was overturned at the Dutchness County Courthouse. Relieved beyond belief, Bozella was free to start his life over and he had one desire in mind. “I was, like, 50-years-old. I just wanted one pro fight. I just wanted to see what I could have been,” said Bozella. He eventually got his wish but as Bozella tells it, “It was hell. It wasn’t easy.”

Prior to and after his prison release, Bozella suddenly became hot commodity when ESPN recognized his story by awarding him with the Arthur Ashe Courage Award at the 2011 ESPY Awards and the following year produced a 30 for 30 documentary called 26 Years: The Dewey Bozella Story. During his ESPYs acceptance speech, he expressed his desire to have one pro fight. Former boxing greats Oscar De La Hoya (Golden Boy Promotions CEO) and Bernard Hopkins (Golden Boy Promotions Partner) got involved to make it a reality for Bozella.

The ESPN TV network recognized Bozella’s steadfastness by presenting him with its Arthur Ashe Courage Award in 2011. Photo Credit- Zimbio.

Bozella set out to obtain a boxing license from the California State Athletic Commission but after he failed the first test, De La Hoya stepped in. Frustration kicked in for Bozella as he felt he wasn’t being given a fair shake because of his advanced age. “After they did all that, they told me I failed,” Bozella explained. “I said, ‘I didn’t fail, you just don’t want me to have it.’ I was pissed. ‘You’re using my age against me. You don’t know what I’m qualified of doing because you’re not giving me a fair chance.’ It was all bullshit.”

With another obstacle thrown at him, Bozella didn’t waiver. He went to the famous Joe Hand Boxing Gym in Philadelphia, where Hopkins trained, for another test. He passed the test and was granted a boxing license. Finally, he would get to fulfill a long lost dream but the preparation leading up to the fight was arduous, especially for an older fighter in a dangerous sport like boxing. Hopkins and his team — who was training for an upcoming fight — took Bozella under his wings and helped train him. If there was anyone who could relate to Bozella’s plight, then it was the boxing Hall of Famer Hopkins, who served five years in Graterford Prison in Pennsylvania for nine felonies before he was released in 1988.

In some ways, Hopkins and Bozella were kindred spirits. “Because of my history of understanding a second, third or even a fourth chance – if your fortunate enough – to get it right in life, not knowing Dewey from anywhere in life and before ESPN did a documentary, I said, ‘Let’s give this man a shot, win, lose or draw of achieving a dream that could have been but wasn’t,’” said Hopkins. “The dream ain’t when it comes true, it’s when you visualize it.”

In training, Hopkins showed him how to preserve his body while running. Bozella learned four-step running up a hill (1-2-3-4 and then two steps) that helped strengthen his legs. “He gave me something I never forgot man. He gave me a lot of information by watching him spar for his fight. I teach other people today some of the information he told me,” said Bozella.

On October 15, 2011, at the age of 52, Bozella was matched up against 30-year-old Larry Hopkins (0-3 pro record, 12 mixed martial arts fights) — no relation to Bernard Hopkins — for his first and only pro fight, at cruiserweight. The bout was on the undercard of Hopkins’ light heavyweight title defense fight versus Chad Dawson at the Staples Center in Los Angeles on HBO PPV. Even the then-U.S. President Barack Obama contacted him to wish him good luck. Hopkins couldn’t have been more delighted.

“I wanted to give him the stage on my card because it wasn’t about ego with me,” said Hopkins. “It was about a comrade overcoming obstacles and getting a chance before time runs out and it made me feel good. I will never forget that moment in my entire life to see how happy he was.” Bozella recalled the Hall of Famer’s pre-fight advice. “Bernard said to me, ‘When you get out there, don’t try to impress the crowd. Just relax and fight your fight.’ That’s why the other guy ran out of gas and I lasted longer.”

Scheduled for four rounds, Bozella seemed tentative in the first round, adding that he foolishingly wanted to stand his ground and slug with his younger opponent. The second round is where Bozella found his rhythm and just boxed, implementing plenty of head and body movement that frustrated Hopkins. “After that, the fight was over,” said Bozella. In a rare occurrence, Hopkins ended up spitting his mouthpiece out six times in the final round which signaled to Bozella and the announcers that he was quitting. “Oh yeah. He didn’t want me to knock him out,” said Bozella. “He saw the knockout was coming and I was coming along stronger. When I caught him with a good body shot, that’s when I knew I had him.”

In his moment of glory that was long overdue, the former inmate shined and won a unanimous decision.

******

Sitting in Alex’s, a restaurant in downtown Poughkeepsie right across from the Dutchness County Courthouse where Bozella was both convicted and exonerated, he takes an introspective look at what has been the most challenging aspect since becoming a regular citizen of society again. “Trusting people,” says Bozella decisively. “Everybody has their own agenda. I’m a good guy. I have a good heart. You get to learn how people are step-by-step when you’re around them.”

As a tough-minded individual, Bozella can certainly be friendly but also guarded, trusting few. Going on 10 years since he was fully absolved from any wrongdoing in his much-publicized murder case, one could assume life would be smooth-sailing this past decade. Not for Dewey Bozella. Plenty of highs and lows have presented itself along the way. He dealt with a divorce in 2016, then remarried in 2019 and now has a two-year-old son. He got the chance to travel the world and experience different cultures. He signed a book deal with HarperCollins Publishing for his autobiography which was a financial success but under a two-year contract restriction, was unable to participate in other interests like public speaking engagements he was accustomed to doing where he was making good money. “I wish I never would have signed that deal because it took me away from things I could have been working on,” said Bozella, looking back. “It was a learning experience. I was very green with a lot of deals I made with people.”

Universal Pictures was planning on producing a movie on Bozella’s life around 2014-15 with Peter Berg (“Friday Night Lights”) set to direct the film but it never transpired. “Universal Pictures let me down. For two years, Berg was trying to do a movie but it never worked out,” said Bozella. “That was a waste.”

However, if there’s one area where he’s found a niche at and holds the same noteworthiness as boxing to him, it’s been his involvement in the last two years to help revamp the criminal justice system by pushing lawmakers in the state of New York to change the current discovery reform laws – the same laws that put Bozella behind bars.

The term “discovery” means how and what information and evidence is exchanged between the parties in a case of pre-trial. In most states, defendants are permitted to see the government’s evidence before trial, however under the current state of New York’s discovery law, defendants are denied access to important evidence and a fair chance to fight the case against them. Because of the major flaws (No Pre-Plea Discovery, Lack of Witness Information, Incomplete Production of Evidence, Nondisclosure of Evidence Favorable to the Defense) in the state’s criminal discovery laws there have been a plethora of cases where innocent people are wrongfully accused of a crime that have devastated the lives of thousands because of sufficient information being withheld by the prosecution during pre-trial.

Those exact inadequate laws burned Bozella twice at trial in 1983 and later in 1990 because of evidence being subdued. Over the last two years – his way of giving back to society – Bozella has been one of the many leading voices in effort to modify the reform laws. Asked why he has been so immersed in this fight, Bozella simply added, “For the system to be fair. It doesn’t matter what color or nationality you are, it’s a matter of fairness. Prosecution attorneys might not like it but you gotta be ready for change. What about the guy you put away for the rest of his life, or the person on death row? What about them? And there innocent?”

Wrongful convictions in the United States have been a steadfast problem for decades. According to statistics assembled by The National Registry of Exonerations in 2019 that tracked wrongful convictions from 1989 to 2019 in all 50 states, showed that countless injustices have led to more than 21,000 years lost in prison for individuals who were later exonerated.

The main contributing factors being false confessions, false accusations, perjury, mistaken identity, official misconduct and bad forensic evidence. In the last 30 years, New York was second in number of wrongful convictions (281) only to Illinois (303), second in murders (123) also to Illinois (156), where people lost a combined 2,716 years in prison with the majority being men (94%) and mostly black americans (53%).

While talking, Bozella uses the word “fair” repeatedly. It’s a word that sticks with him. Haunts him almost. “Fair” worked against him for 26 years. Now it comes back into play again, this time to benefit others from dealing with the same fate he suffered. “I’m not looking into being the main spokesperson,” said Bozella, a board member of The Innocence Project, a nonprofit legal organization committed to exonerating wrongfully convicted people. “I’m just willing to put myself out there to do the right thing.”

To the delight of advocates of the law, a change was announced on April 1, 2019 where New York State Legislature passed a law that would require prosecutors to turn over all their evidence to the defense within 15 days of a defendant’s first court appearance, as part of a collection of criminal justice system initiatives such as elimination of the cash bail system, introducing a true discovery motion and to protect speedy trial. New York became the 46th state to adopt similar open discovery laws. The new laws officially went into effect on January 1, 2020.

Marvin Mayfield, a New York State Organizer for Just Leadership, a national advocacy organization promoting criminal justice reform in the country and mission is to decrease the United States prison population in half by 2030, met Bozella and asked him to speak at a October 28th hearing in Albany, New York in front of district attorneys and lawmakers, who both supported and were opposed to the law. Also in attendance was New York State Senator Jamaal T. Bailey.

“Dewey’s presence there was to persuade the opposition, or at least, to enlighten them how people are directly impacted by the practices they have been perpetuating in the state of New York for generations,” said Mayfield. “His story was very compelling how he spent 26 years behind bars because of police misconduct and he was fully exonerated. Those are the stories we want to amplify. In Dewey’s case, the evidence against him was suppressed, which is typical of what New York state prosecutors have been doing. They have always held all the cards. His case exemplified that these prosecutors do not cooperate and operate within the letter of the law by denying the person the rights to the evidence against them. His story is an example, but not unique, because there are so many others who have also been abused and lives have been wasted because of how the criminal justice system so unfairly and disproportionately affects black people in this country.”

Sen. Jamaal Bailey, Codes Committee Chairman, questions speakers during a state Senate hearing on the new pre-trial discovery reform rules on Monday, Oct. 25, 2019, at the Legislative Office Building in Albany, New York. The new laws took effect on January 1, 2020. Photo Credit- Will Waldron/Times Union

Bailey, the Chairman of the Codes Committee (deals with issues on criminal justice) and the sponsor of the new discovery reform bill, was appalled by the grotesqueness of Bozella’s story. “It was one of shock, bewilderment and surprise. It showed that this is a person that embodies why the laws need to be changed and I’m glad we did change them,” said Bailey, who has long been a proponent of changing the reform laws which he said has been in place for decades. “The reforms we made that will take into effect in January in my belief were common sense and long overdue but when you hear a story like Mr. Bozella’s, it’s like the perfect storm.”

A firm reason for optimism can be traced to the national rise in exonerations since 1989, particularly in the state of New York, where they have been 281 exonerations, the third-most behind Texas at 363 exonerations.

Both Mayfield and Bailey said that the group present that night were moved when Bozella came to speak. “When Dewey spoke, there was a lot of focus on him and not only for those people who supported but for those who were against this legislature being implemented,” explained Mayfield. “You could visibly see that his story touched people and the way he conveyed it with such passion and genuineness, you could tell every word he was speaking was the truth. In this society, people don’t believe anything unless it’s in black and white. Dewey lends credibility to the claims he made. He is what we call a credible messenger.”

“Just from looking at the individuals around that were there, they seemed to be shocked and amazed wondering how in such a progressive state can something like this happen to anybody, much less Mr. Bozella,” said Bailey. “It hugely impacted me. It took him so long to get justice. His courage was amazing. He never gave up. He never plead to something he didn’t do. Everybody doesn’t have that same level of courage.”

Bernard Hopkins (far left) was instrumental in Bozella getting a boxing licence to box again. Also in the picture is Hopkins’ assistant trainer Danny Davis (to the right of Bozella) and trainer Rick Chavis (far right) at the famous Joe Hand Boxing Gym in Philadelphia. Photo Credit- Joe Hand Boxing Gym

Hopkins, who has been critical of how unjustly black men have been treated by the criminal justice system in America, says Dewey should be looked at as a symbol of hope. “I believe there is a percentage of men sitting in jail because of a lack of a lot of things. That’s the proper representation, resources and due process, and not bias process. I salute the brother to this day and any inmate out there that’s facing adversity, Dewey Bozella should be looked at as the poster man of redemption.”

******

Nowadays, Bozella is a man of many parts. Public Speaker. CEO of music label Young America Entertainment. One of the lead actors on an independent TV show called Fight City, where he plays a former fighter who is an underground character. John Lee, one of the producers/writers for the show says what surprised him the most about Bozella’s acting ability was his aptness to improv. “Extend the scene pass the dialog. As someone who’s playing an underground character, you want someone who’s not overacting,” said Lee. “You want people to be as authentic as they can and he does that really well because he understands his role and his position. He brings a lot of truth to his character.”

Bozella acting in a scene on the set of Fight City, which films in Harlem, New York. Photo Credit- IMDb

Still, at the core of everything he’s involved in, boxing remains supreme in his life. He wants to be a trainer and a promoter. He was looking into opening up his own boxing gym, ironically enough, on 15 Hamilton Street in Poughkeepsie – the location of the murder – but it didn’t fall through. Now he’s looking into locations in New York or even thinking about heading to Atlanta to find the right destination. He attends fights regularly at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn, where he’s seen world champion fighters like Deontay Wilder, Shawn Porter, Keith Thurman and Andre Berto in the ring.

He likes debating boxing. He could go on for hours. He’ll talk about everything from his favorite current fighter, Vasyl Lomachenko (“When I saw him for the first time on TV, I knew he was special”) to, why he sees Canelo Alvarez versus Errol Spence as boxing’s next superfight at middleweight (“Spence can make the necessary weight at 160 and has the skills to beat Canelo, who is like the Sugar Ray Leonard of this time”) to, his candid thoughts on Floyd Mayweather, Jr. (“Floyd is a good fighter, don’t get me wrong. His style worked for him in this era but against a young Roberto Duran, Alexis Arguello at lightweight, Tommy Hearns, Sugar Ray Leonard and Aaron Pryor that shit wouldn’t have worked”) to, how he thinks the inflation of divisions and belts has hurt the sport (“Now we have too many divisions and I don’t know how many damn belts. It’s confusing to the fans.”)

Through all the tribulations he’s experienced, the sweet science has been right by his side and he gives thanks. “Boxing was and still is my saving grace to this day.”